Water security in 'desert' Rajasthan

Water security is not determined by nature alone. Culture, social structures and tradition play an equal part in ensuring water security in low rainfall regions such as Rajasthan. Anupam Mishra's landmark book on traditional water harvesting and storage systems in Rajasthan is now available in English translation

By general consensus, the one resource that is most likely to engender social conflict in the 21st century is water. Every resource is under pressure as the world becomes increasingly 'developed', globalised and overpopulated, with drastic consequences on the environmental balance of the planet. But it is water resources in particular, that have been coming under increasingly severe pressure in recent years. As it is, we have a very limited supply of fresh water, with less than 1% of the water on the planet fit for human use; and our short-sightedness has ensured that we have polluted and mismanaged the little that we do have. It is not for nothing that dire predictions of future 'water wars' are becoming common, not only in development discourse but in mainstream circles as well. Disputes over water resources, at the local level, at the inter-state level (eg over sharing of riparian waters), and at the national and international levels are only growing.

But is the availability of water the only issue, or is the way water is managed at the community and individual levels equally crucial? What role does traditional knowledge and wisdom have to play when it comes to harvesting and sharing of water? Is there any way out of the dead-end that expensive, large-scale projects like dams have led us into? Why is it that many sustainable traditional methods of water conservation are suffering the ravages of neglect? Is there any way this trend can be reversed? The Radiant Raindrops of Rajasthan draws our attention to these vital issues. This book was originally published in Hindi as Rajasthan Ki Rajat Boondein and went on to become a modern development classic. With its lyrical language, and deep commitment to traditional values and methods, it had a deep impact on current thinking on issues of water conservation and harvesting. The Research Foundation for Science, Technology and Ecology and its Director, Maya Jani, who has translated the book into English, have rendered an important service to those who cannot read the book in the original.

Anupam Mishra's landmark book on traditional water harvesting and storage systems in the 'desert state' of Rajasthan convincingly demonstrates that water security is not a given of nature; rather, it is a combination of nature with culture, social structure and tradition. Thus we see that many regions receiving high rainfall are actually water scarcity regions, while regions receiving low rainfall may have adequate water security.

Rajasthan is a classic example of the latter situation. Receiving very low amounts of rainfall (putting it at the borderline of the definition of desert), even the little rain that does fall is concentrated in just 3-4 months every year. Yet Rajasthan belies the image of a desert region, and this is because society here has developed and nurtured a very strong tradition of water conservation, which, though weakened, has not been entirely swept away by the waves of modernisation and the dubious technologies it has brought in its wake. The tradition of conserving every drop of water has stood Rajasthan in good stead, and agriculture flourishes in many parts of the state. Households, even in the most arid parts of the state, have access to sufficient water for their needs round the year. Little wonder then that the value ascribed to each drop of water leads Mishra to describe them as 'rajat', which means silver and also ivory in Hindi.

The structure of the book is such that it introduces us step-by-step to the variety of traditional water conservation structures and traditions. After an initial chapter which introduces the state of Rajasthan and its chief characteristics, and another which introduces us to the religious, cultural and spiritual connotations of water conservation and its traditions, each chapter in the book describes a homogeneous set of structures for water conservation and harvesting. These include kuins (deep, narrow wells which access the capillary water trapped between the brackish water table and the surface), kunds (ponds) and tankas (tanks) - ranging from small household-level structures to gigantic structures which supply the needs of entire towns - and ponds and retention pools, from the smallest structures to the enormous talabs like those of Gharsisar.

The agriculture of the khadeens is described; khadeens are oases which are created through the retention of water in the beds of seasonal rivers, and enable two crops, kharif and rabi, to be taken. Another chapter discusses the techniques of boring and coating, and describes in detail the tools used to draw water - water skins, pulleys and the like. The brief final chapter compares Rajasthan with other water-scarce regions in other developing countries. This chapter gives an indication of how the Rajasthan model can show the way out of water-scarcity by self-managed traditional techniques, developed and designed keeping in mind local conditions and resources.

The book underscores the fact that we have much to learn from our traditions as we confront a whole range of ecological and social problems. In the area of water conservation, much work has already been done. One of the lasting legacies left by environmentalist Anil Agarwal has been the work done by the Centre for Science and Environment in uncovering and highlighting our water conservation traditions, as well as in promoting environment-friendly technologies for water conservation and use.

As the evils of many of our technological solutions become increasingly evident, a movement for the use of traditional environment-friendly technologies is building up. The modern Indian state has largely been geared towards expensive, technology-intensive, large-scale solutions to problems of water availability. The thinking that led Jawaharlal Nehru to describe large dams as 'temples of modern India' still rules the roost, and has created disaster after disaster, all in the name of development. The Narmada project is but one example, but unfortunately it may not be the last or the least; the current inter-linking of rivers project is the prime contender for the accolade of the most hare-brained scheme of them all. This scheme will seek to reverse geography and the entire logic of catchment areas and river basins; it is a foregone conclusion that it will create displacement, misery and environmental disaster on a scale that far outweighs its purported benefits. In Rajasthan itself, the Indira Gandhi Canal has failed to deliver most of the benefits which it was designed to bring, and has in fact created an entirely new range of environmental problems.

Of course, any argument against these large-scale, technological solutions cannot rely on logic alone. It is more than likely that the proponents of such schemes are entirely aware of the flaws in their proposals. But there is a consensus among India's elites in favour of these projects, not because of their appropriateness or soundness, but because these expensive, resource-intensive projects are the basis of the 'loot-economy' on which our elites thrive. The proliferation of such projects can only be halted once strong grassroots movements, which bring control of development into the hands of the people, come up and strengthen themselves to present an alternative vision.

Work which highlights indigenous traditions can help in this process - Anupam Mishra's work on water conservation in Rajasthan has not remained confined to the libraries; it has inspired a range of efforts in Rajasthan to research and revive traditional methods of water harvesting. The Tarun Bharat Sangh in Rajasthan has initiated a grassroots movement to revive these traditional structures. The work has received much acclaim and inspired many similar efforts in other parts of India.

One weakness of the book, though, is one that bedevils much of the literature that seeks to celebrate 'tradition', which is that it takes a rather uncritical and rosy-eyed view of the past. The social structure of Rajasthan receives uncritical approval, on the somewhat dubious grounds that a society which gave rise to and nurtured such a fantastic water conservation system must have been good and just. This is somewhat like saying that slave societies were a good idea, because they produced marvels like the Egyptian pyramids.

More discernment is called for. There is good and bad in all societies, and we would be doing ourselves a disservice if we seek to lay the blame for all our problems on our colonial past, and hark back to a bygone golden age for the solution to all our problems. This concern becomes all the more urgent, given the rise of fundamentalist and obscurantist forces in the political firmament of India. It is only with a judicious combination of tradition and modernism that we can hope to successfully tackle our problems, be they environmental, social or political.

The book also succeeds to a certain extent in conveying the lyrical, poetic quality of the original, no mean feat. One wishes, though, that this were not at the expense of grammar and punctuation, which very often jars quite badly. Also, place names are inconsistently spelt, and districts mentioned in the text do not make an appearance in the tables, leading to some confusion.

These flaws do not detract from the urgent, passionate message that Mishra has for us. The only means for sustainable resource management is when people and communities take control of their resources, and use them equitably with due concern for environmental issues. Anybody who wants to know how traditional knowledge and wisdom can contribute to this process in the area of water harvesting and conservation needs to read The Radiant Raindrops of Rajasthan.

By Vidyadhar Gadgil

(Vidyadhar Gadgil is an independent writer and editor based in Goa.)

http://infochangeindia.org

Dhan, Madurai

Development of Humane Action (DHAN) Foundation, a not-for-profit development

organisation, was initiated in October 1997 and incorporated under Indian Trusts Act (1882), in January 1998. DHAN Foundation is a spin off institution of PRADAN

(Professional Assistance for Development Action based at New Delhi) one of the country's foremost development agencies. The Trust has been promoted with an objective of bringing highly motivated and educated young women and men to the development sector so that new innovations in rural development programs can be brought and carried to vast areas of the country and the people, especially the poor.

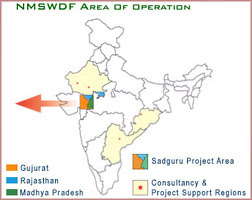

Area of operation:

www.dhan.org

JAL BHAGIRATHI FOUNDATION, JAIPUR

Jal Bhagirathi Foundation is a trust committed to the principle of participatory management, where the work belongs to the community with the role of JBF being limited to that of a catalyst and facilitator.The project in the Marwar region is a Natural Resource Management Project with special emphasis at building the capacities of backward rural communities for management of critical water resources. While the project seeks to support traditional institutions of managing common property resources, it seeks to decrease biotic pressure on the fragile eco-system. The project will provide drought relief to a region extremely distressed with repeated droughts and also focus on community driven solutions for long term drought proofing of the Project Area. The methodology for implementation of projects as adopted by JBF is as follows. Firstly, public meetings and padyatras (walks) through villages and local workshops are organized in the target area. As a result of these initiatives, the village community is mobilized to form a Jal Sabha or user association of all those who are willing to participate in the proposed work. This is followed by the election of office bearers who act on behalf of all the members of the Jal Sabha and undertake the execution of the work and mobilization of community resources. The Jal Sabha then designs the water harvesting structure and decides on the form of the village contribution for the work. The Jal Sabha also forms a woman's group to ensure women's participation in the decisions and also to create women's platform for community activity. Community resources are mobilized in the form of labor, material and cash towards the development of the community water harvesting/recharge structures. All the structures under this initiative are need-based with the active participation of the community in all stages of construction: from identification of the site to the design of the structure and by a contribution of one-fourth of the cost of their construction through 'shramdaan', material or cash. Community management will ensure equal distribution of the resources and their benefits.

http://www.jalbhagirathi.org

NM SADGURU FOUNDATION DAHOD

Established in 1974, Navinchandra Mafatlal Sadguru Water Development Foundation is a non-governmental organisation which is non-political, non-profit making, secular organisation registered under the Public Charitable Trust Act, the Societies Registration Act (1860) and the Foreign Contribution (Regulation) Act. It is recognised by the Department of Rural Development of the government of 3 states of Rajasthan, Gujurat and Madhya Pradesh.

Its main objectives are to improve the living condition of rural and tribal prople by developing environmentally sound land and water resources programmes; improve the environment; arrest the distress migration; improve the socio-ecomonic status of rural prople and strve for their overall development. This is prompted by facilitating the growth of local institutions that support and sustain the NRM Programmes.

Website: http://www.nmsadguru.org/

WATERSHED ORGANISATION TRUST, AHMEDNAGAR, MAHARASHTRA

The Watershed Organisation Trust (WOTR) was established in December 1993 as a support organization for Village Self Help Groups (VSHGs) and NGOs implementing watershed development projects. It assists people living in rural areas alleviate their poverty through participatory natural resource management on a watershed basis. WOTR was established primarily to respond to the needs expressed by partners in the lndo-German Watershed Development Programme (IGWDP).

WOTR assists NGOs/VSHGs by providing technical support in planning, project formulation, implementation, documentation, monitoring and evaluation of their watershed projects. WOTR initiates capacity building by supporting NGOs / VSHGs to undertake the planning, organization and implementation of a small micro watershed within the larger watershed. This becomes the forum for a reflective learning process for these implementing groups.

Website: www.wotr.org

NEERJAAL Tilonia Rajasthan

ABOUT NEERJAAL

ABOUT NEERJAAL

NeerJaal is a concept originally conceived by the Barefoot College in Tilonia OR Social Work and Research Centre (SWRC), Tilonia in Rajasthan. SWRC, under its flagship activities of Barefoot College, has been collecting and managing information regarding various linkages of Water in the desert of Rajasthan, especially in and around tilonia village near Kishangarh . Recently, SWRC, together with Digital Empowerment Foundation, discussed the NeerJaal concept together and developed the entire concept to implement at the national level, where the water sources, water bodies, water consumption, water usage, water harvesting, and water shorateges and needs could be mapped and put on an interactive platform.

The long term vision of NeerJaal is to allow each and every villagers and villages to put their water data on the public domain, and gradually with as the help of people and universal contribution, we gather widespread data related to water in India.

At the moment, the data is being populated through the available information with SWRC, and gradually with the launch of the website, this would be made open to all and sundry to populate the relevant information. However, each and every information would be updated after proper administrative and authentication check. ABOUT DEF

ABOUT DEF

Digital Empowerment Foundation, a Delhi based not-for-profit organization was registered on December 2002, under the "Societies Registration Act XXI of 1860" to find solutions to bridge the digital divide. With no political affiliations, it was founded by Osama Manzar to uplift the downtrodden and to create economic and commercial viability using Information Communication and Technology as means. It was actively started in the year 2003 after the founder director left his software company to seriously pursue the aims and objectives of Digital Empowerment Foundation.

ABOUT SWRC/BAREFOOT COLLEGE

The Barefoot College began in 1972 with the conviction that solutions to rural problems lie within the community.

The College addresses problems of drinking water, girl education, health & sanitation, rural unemployment, income generation, electricity and power, as well as social awareness and the conservation of ecological systems in rural communities.

The College benefits the poorest of the poor who have no alternatives.

The College encourages practical knowledge and skills rather than paper qualifications through a learning by doing process of education.

The College was entirely built by Barefoot Architects. The campus spreads over 80,000 square feet area and consists of residences, a guest house, a library, dining room, meeting halls, an open air theatre, an administrative block, a ten-bed referral base hospital, pathological laboratory, teacher's training unit, water testing laboratory, a Post Office, STD/ISD call booth, a Craft Shop and Development Centre, an Internet dhaba (cafe), a puppet workshop, an audio visual unit, a screen printing press, a dormitory for residential trainees and a 700,000 litre rainwater harvesting tank. The College is also completely solar-electrified.

The College serves a population of over 125,000 people both in immediate as well as distant areas. Social Work and Research Centre Tilonia, Rajasthan, India.

CONTACT DEF

The Director

Digital Empowerment Foundation

12/17, Lower Ground Floor,

Sarvpriya Vihar,

New Delhi 110017, India.

Ph: +91-11-26532786

Fax: +91-11-26532787

E-mail: defindia@gmail.com | Website: www.defindia.net

CONTACT SWRC/BAREFOOT COLLEGE

The Director

The Barefoot College

Village Tilonia,

via Madanganj, District Ajmer,

Rajasthan 305816, India.

Ph: +91(0)1463-288204

Fax: +91(0)1463-288206

E-mail: barefootcollege@gmail.com | Website: www.barefootcollege.org

Sanctuary Asia,

Sanctuary Asia, India's leading wildlife, conservation and environment magazine, was started by Editor Bittu Sahgal in 1981 to raise awareness among Indians of their disappearing natural heritage. The overwhelming response to the magazine led to the birth of Sanctuary Cub, a children's nature magazine, in 1984 and to The Ecologist Asia (Indian edition of The Ecologist, U.K.) a journal dedicated to the issues of the environment, development and human rights, in 1993.

In the 1980s, Sanctuary Films produced two wildlife/conservation serials aired on Doordarshan, India's national television network. The first, Project Tiger, was a documentary while the other, Rakshak, was a narrative serial for children. The films were shot on 16 mm. and the Sanctuary team visited virtually every wildlife haven in India (stock footage available on request).

In the early 1990s, Sanctuary's scope expanded. We began to reach out to larger numbers through the syndication of articles. Sanctuary Features was born and it used the mainstream press to put forward alternate views on wildlife and development issues. Features covered a variety of subjects including travel, science, health, nutrition and the politics of development. Sanctuary Features is now also a leading content provider for websites interested in the above subjects.

Sanctuary Photo Library, our stock photo agency, has a fully computerised database of images that are available on request. Our focus is on Indian/Asian natural history and is used by academicians, picture researchers for publications, non-profits, websites, advertising agencies and corporate communicators. Sanctuary is a melting pot of natural history visuals, information and resources and these are put to good use to produce some of the finest wildlife and nature calendars, posters, slide shows, exhibitions and other products available in India. These high quality products can be made available at reasonable rates and can be delivered anywhere in the world.

Sanctuary Cub reaches out to children across India through schools and nature clubs. We conduct nature walks, camps, slide shows and rallies for children with the help of qualified naturalists and environmental educationists.

Sanctuary is at the fulcrum of several wildlife conservation campaigns and serves as a network for wildlife groups, concerned individuals and non-profit organisations. It is also a source of information for press and television reporters.

Sanctuary’s Kids for Tigers, an environmental education programme in schools across India, aims at increasing awareness among children about the nation's biodiversity and sensitise them to the fact that saving tigers and forests will secure water supply and help save ourselves. Through 'edutainment' workshops, exciting tiger fests, thought--provoking film shows and nature walks, Kids for Tigers leaves children and teachers enthralled with the world of nature and wildlife. The programme is in its 5th year and is an integral part of 1,000 schools all over India.

In 1999-2000, Kids for Tigers collected one million signatures in support of the tiger. The Limca Book of Records certified this as the world's largest 'Save the Tiger' scroll.

In summary, the organisation could be described as one that aims to communicate the rationale for wildlife conservation and environmental protection. Our focus is the Indian subcontinent and Asia, but our horizon spans the globe. Sanctuary is a privately-owned, self-supporting venture and does not accept any donations. Its funding sources are advertisements, subscriptions and content provision.

For all enquiries by regular mail, phone or fax contact:

Address 145/146, Pragati Industrial Estate,

N.M. Joshi Marg,

Lower Parel,

Mumbai – 400 011

Tel. (91-22) 2301 6848 or 2301 6849

Fax (91-22) 2301 6848

http://www.sanctuaryasia.com/

Kalpavriksh

Kalpavriksh believes that a country can develop meaningfully only when ecological sustainability and social equity are guaranteed, and a sense of respect for, and oneness with nature, and fellow humans is achieved.

Delhi:

Kalpavriksh

134, Tower 10,

Supreme Enclave

Mayur Vihar

Phase 1

Delhi 110 091

Tel: (011) 22753714

http://www.kalpavriksh.org/

Kalpavriksh

Kalpavriksh believes that a country can develop meaningfully only when ecological sustainability and social equity are guaranteed, and a sense of respect for, and oneness with nature, and fellow humans is achieved.

Delhi:

Kalpavriksh

134, Tower 10,

Supreme Enclave

Mayur Vihar

Phase 1

Delhi 110 091

Tel: (011) 22753714

http://www.kalpavriksh.org/